I Will Walk Across the Air to You

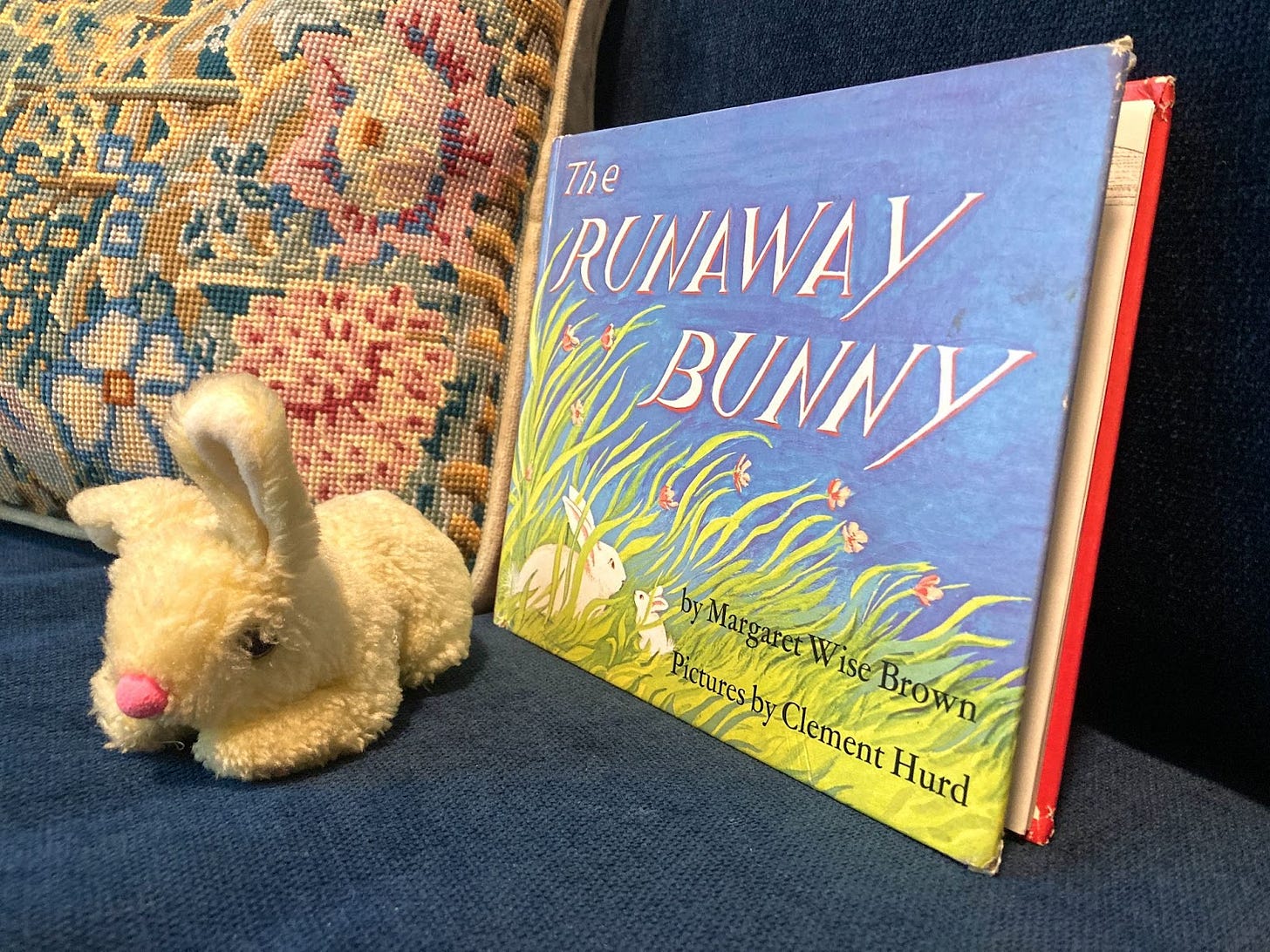

The Runaway Bunny by Margaret Wise Brown and illustrated by Clement Hurd

Salutations, bibliophiles.

Today, I’m very excited to bring you Maddie Burton.

Maddie writes On The Cusp, where she explores personal growth and becoming.

The essay Maddie has written for us is a deeply personal and heart-wrenching account of the book that helped her during the final few months of her mother’s life. Through Maddie’s beautiful words, we are once again reminded of the power of literature, even—or especially—when that literature is a children’s book.

For the first time since entering home hospice care, my mom has ventured outside her bedroom.

She’s attached to portable IV pumps that deliver pain medication to the central veins around her heart. Theoretically, the carrying-case straps can be slung over her shoulder like the world’s saddest backpack. But until today, the meds haven’t masked the pain well enough for her to navigate stairs.

That’s why I’m overjoyed to find her on the ground floor of her three-story townhouse, chewing Bazooka bubblegum and giving a home tour to her health aide. Monique already knows the lay of the land; still, she humors her hostess and ward.

“This is my favorite room in the whole house,” my mom announces, sweeping her arm toward the shelves full of children’s books. “It’s my happy place.”

One of our favorite books on that shelf is The Runaway Bunny, written by Margaret Wise Brown and illustrated by Clement Hurd.

It tells the story of a young rabbit’s attempts to assert his independence. Each time he threatens to create space between them, his mother details how she’ll fill it. Regardless of how he might try to escape, she’ll find a way to close the distance.

Once there was a little bunny who wanted to run away.

So he said to his mother, “I am running away.”

“If you run away,” said his mother, “I will run after you. For you are my little bunny.”

“If you run after me,” said the little bunny, “I will become a fish in a trout stream and I will swim away from you.”

“If you become a fish in a trout stream,” said his mother, “I will become a fisherman and I will fish for you.”

In recent months, the mother bunny’s reassurances have taken on new, bittersweet meaning. My mom is about to die, and when that happens, I don’t know where or how we’ll find each other.

When she found out she was pregnant with me—her first child—my mom was in Washington, D.C. on a business trip. After the pregnancy test came back positive, she visited her hotel gift shop.

That’s where she bought my first stuffed animal: a small yellow bunny with glass eyes and a neon-pink nose, one ear sticking straight up, the other flopping over the left side of his face.

Given his place of origin, he was henceforth known to our family as D.C. Bunny.

“If you become a fisherman,” said the little bunny, “I will become a rock on the mountain, high above you.”

“If you become a rock on the mountain high above me,” said his mother, “I will be a mountain climber, and I will climb to where you are.”

As her pain worsens, my mom experiences a minor spiritual crisis. It’s been a hard day, and with harder days ahead, she wants to know that her own mom—who died six years earlier—is by her side.

She’s mentioned that she talks to her departed parents, but this is the first time I’ve seen her do it. “Mom, wherever you are, give me a sign,” she pleads, looking at the ceiling as if to the heavens.

“If you become a mountain climber,” said the little bunny, “I will be a crocus in a hidden garden.”

“If you become a crocus in a hidden garden,” said his mother, “I will be a gardener. And I will find you.”

We have company for dinner. The rest of us eat takeout tacos; my mom eats a slice of cheesecake with her hands, as if it were pizza. Our friend Armando explains his family’s belief in visitations from departed loved ones, and relays his own visceral experiences with the phenomenon.

The hospice rabbi visits the next day; my mom asks if the Jewish tradition supports this idea of ghostly visitations. She isn’t entirely comforted by his response, and continues seeking answers elsewhere.

When our friend Janet drops by, my mom inquires about her psychic. Maybe we could hire her to host a Zoom seance, and connect with my grandmother in the afterlife?

In the exact moment my mom poses this question, the candle burning nearby explodes, sending shards of glass scattering like shrapnel.

The hard days arrive with increasing frequency. My mom’s pain is excruciating, despite her rapidly-increasing pain medication dosages.

The uncertainty is unbearable, too. Dying from terminal cancer is like being strapped to a ticking bomb, but nobody can see how much time is left on the clock.

Still, I’m caught by surprise when she locks herself in the ground-floor bathroom and swallows all the drugs she has access to. I run downstairs, alongside her inconsolable health aide, and we beg her to open the door.

“Just let me go,” she says, crying. “Please.”

By the time first responders arrive, she’s opened the bathroom door and walked twenty feet down the hall, where she sits on the green patterned loveseat across from the children’s bookshelves.

Now, she’s crying because she doesn’t want to be taken away. She’d wanted to die at home, not under 24-hour psychiatric watch in a hospital room.

I sit facing her, my back to the hallway. My focus narrows; I don’t notice the room filling up with the police, parademics, and firefighters we’d summoned with our 911 call.

When I finally turn around, I count at least a dozen men packed into the tiny room with us, hands folded, heads bowed. Silently, respectfully, they’ve watched me convince her to get inside the waiting ambulance.

By the time we arrive at the ER, she’s unconscious. There’s nothing to do now but wait and see whether she’ll come back.

“If you are a gardener and find me,” said the little bunny, “I will be a bird and fly away from you.”

“If you become a bird and fly away from me,” said his mother, “I will be a tree that you come home to.”

I return to the hospital each morning in time for doctors’ rounds. In the afternoons, my mom’s cousin Susan relieves me for a few hours.

During these afternoon breaks, I force myself to eat. I launder the nightgown she wore to the hospital so it smells more like Tide and less like Ativan and Dilaudid. Mostly, I sit in her empty house on the green patterned loveseat, read The Runaway Bunny, and cry.

As I flip through its pages, I consider how our mother bunny and little bunny roles have reversed. In this season of our shared life, my purpose is to care for her—to put her needs first.

She doesn’t want to regain consciousness; she’s ready to go. And yet I can’t help wanting her to come back to me, so that we can say a better goodbye.

“If you go flying on a flying trapeze,” said his mother, “I will be a tightrope walker, and I will walk across the air to you.”

On day five of her hospitalization, she’s shown no signs of returning. Her doctor doesn’t expect that to change.

So when she wakes up that evening—long enough for me to say one final “I love you,” for her to respond “I love you more”—it’s confirmation that her doctor’s top-notch medical education wildly discounted the power of a mother’s love.

“Shucks,” said the bunny, “I might just as well stay where I am and be your little bunny.”

And so he did.

My mom told me and my brother that she didn’t care about being buried anyplace in particular. “You know that I’ll be with you two, wherever you go,” she’d assured us.

A lot of things were uncertain about the process of dying, but for her, this wasn’t one of them.

Still, whenever I need something more concrete, I’ve figured out where I can find her: in the cotton-tailed rabbit families that hop through my backyard, in D.C. Bunny, and in her copy of The Runaway Bunny—which now sits on my own bookshelf, my happy place.

P.S. For more ways of getting your writing in front of new readers, consider becoming a paying subscriber today.