Bank your memories

Because some accounts can’t be overdrawn

Your Five-Year Plan is a newsletter about embracing life’s profound uncertainty.

Maybe your own plans went up in flames; maybe you’re considering a big, scary leap. This is your trusty companion while you’re writing the next life chapter.

Welcome to the conversation—and to the adventure that unfolds when your plans go sideways. This is letter #7. ✨

☀️ How was your week?

Last week, paid subscribers received a special edition of the newsletter. We talked about the gifts we gave our Present and Future Selves in May. As for mine:

A sabbatical that doesn’t wreck my financial future. I talked about why I’ll be taking intentional time away from the 9-to-5, how I’m funding that time, and how I’m thinking about the impact on Future Maddie.

Tackling my portion of the estate-settling process, without letting it take over my life. When someone dies, the emotional impact on their loved ones is usually discussed openly. Because the administrative and financial details are so rarely talked about, it felt important to touch on those, too.

On to today’s letter!

Bank your memories

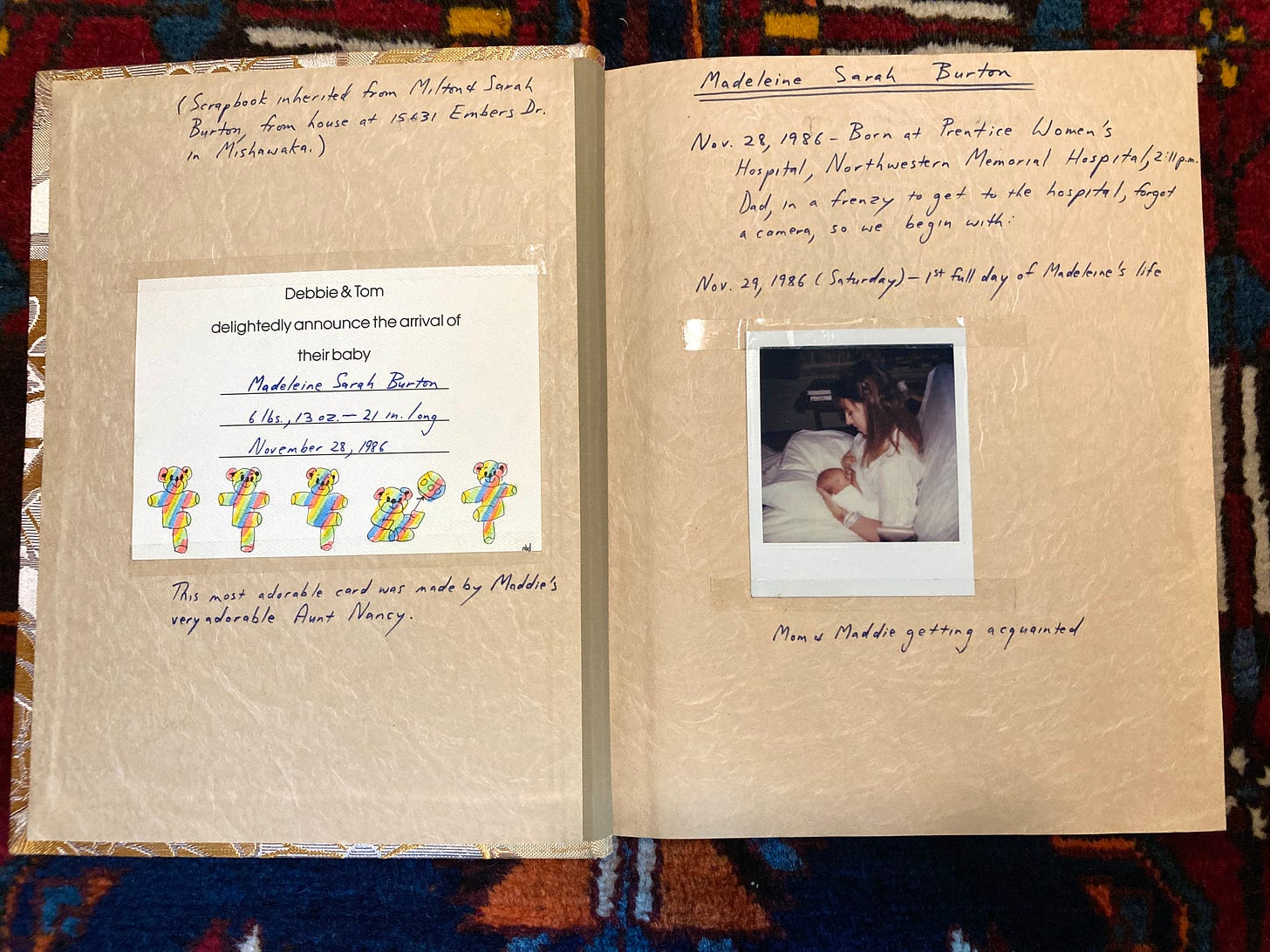

When I found the scrapbook, its padded cover embroidered with golden thread, I knew I’d stumbled across a hidden treasure.

My mom was the queen of photo albums, and the dozens she’d made were easily accessible on a first-floor bookshelf. I’d flipped through them all many times before—almost all of them, apparently. I could tell at first glance that this one was different: precious, tucked-away, pristine.

I opened the cover to find Polaroids I’d never seen from my first days on Earth, infant Maddie in my mom’s arms, accompanied by my dad’s heartfelt and humorous inscriptions. My mom’s hospital bracelets were tucked into the binding; every congratulatory card and letter they’d received was secured in the album’s pages.

Carrie, who was helping us go through my mom’s house, was in the room when I discovered it. We marveled over the pages together.

“Can you imagine anyone taking the time to do this today?” she asked, knowing full well what the answer was. “When did we all get so busy?”

Most of the TV I watch is utterly forgettable, one throwaway episode of Selling Sunset after another. (You know the drill.) But there’s a scene from Mad Men that’s stayed with me through the years—and if you need a good cry, it’s worth a few minutes of your time.

Ad exec Don Draper is standing in a conference room with the team from Eastman Kodak. They’re trying to market their new slide projector wheel, and Don is tasked with earning their advertising business.

Don, who’s going through serious challenges in his own family life, begins his pitch in a darkened room.

“In Greek,” he says, “nostalgia literally means the pain from an old wound. It’s a twinge in your heart far more powerful than memory alone.”

The slide projector begins whirring through moments from earlier, more optimistic days in his marriage.

“This device isn’t a spaceship—it’s a time machine,” he continues. “It goes backwards and forwards. It takes us to a place where we ache to go again. It’s not called the Wheel; it’s called the Carousel. It lets us travel the way a child travels: around and around, and back home again, to a place where we know we are loved.”

It’s the best description of the power of photography I’ve ever heard.

In 2011, I started bringing my film camera to the Thanksgiving table.

I had taken years of darkroom photography classes—beginning in junior high, continuing through college—and had just rediscovered my passion for film after a few years of halfheartedly snapping digital photos.

That passion was reignited when I purchased a Yashica Mat 124G from a stranger on eBay, which was essentially a poor man’s Rolleiflex: a twin-lens reflex camera designed to be held at your waist, and manually focused while looking down through its top-mounted viewfinder.

I didn’t know it at the time, but documenting my family gatherings in black-and-white was the start of something important. It marked the beginning of an era in which I’d bank all my most important memories by shooting them on film.

I won’t subject you to the science of what makes film photographs especially beautiful (although I swear, it’s fascinating!). But I was enthralled by film’s inherent limitations: it offered me a finite number of shots per roll; each shot required me to use a handheld light meter for best results; and each roll cost me somewhere in the neighborhood of $30(!) to buy, develop, and scan.

So if I was going to take a photograph, it had to be worth the effort and price. That forced me to be present in the life experiences I weighed capturing.

Due to the care and discernment it demanded, film photography became the best method I knew for crystallizing experiences into memories—not in spite of its limitations, but because of them.

When you become a financial planner—regardless of how much professional training you undertake—you’ll bring your own personal biases about money into every relationship and conversation. Therein lies an interesting paradox: as you gain awareness and a deeper understanding of your biases, the closer you can approach (though you’ll never actually reach) the asymptote of neutrality.

So as part of my professional development, I chose to read books that challenged, rather than confirmed, my own biases. This is how I found myself with Bill Perkins’ provocative (and provocatively-titled) Die With Zero in hand.

I didn’t agree with all of Perkins’ arguments; I hadn’t expected to. But I found myself surprised by how much his perspective ended up reshaping my own—in particular, on the topic of “memory dividends.”

Perkins argues that memories are subject to similar rules as compound interest. The earlier in life you invest in experiences—and the more enjoyment you get out of them in future years, by reminiscing over photos and retelling stories with friends who were along for the ride—the richer in memory dividends you’ll be.

Perkins describes a moment at the end of his dad’s life, when he’s too weak to travel, but he can time-travel through the happy memories of his college football career through a highlight reel on his iPad.

“That was when I realized that you retire on your memories,” Perkins says. “When you’re too frail to do much of anything else, you can still look back on the life you’ve lived and experience immense pride, joy, and the bittersweet feeling of nostalgia.”

When my grandmother was suffering from dementia, I helped my mom put together a photo book at her memory-care facility’s recommendation: snapshots from my grandmother’s youth, family portraits, photos I’d taken at her 90th birthday party.

When my mom entered home hospice care, I knocked on her door more than once to find her sitting in a chair by the window, flipping through that same photo book, a serene smile on her face.

Recently, I read Shirley Gubler’s memorable contribution to The New York Times’ “Tiny Love Stories” feature, a piece about her grandson:

“After years of waiting and hoping, I became a grandmother in my mid-60s. I looked forward to doing so many things with Dashiell. I would be the most attentive, fun and active grandmother ever! But that changed two years after Dashiell was born, when I was diagnosed with terminal esophageal cancer. I don’t make plans anymore. Now, I focus on spending as much time as I can with this precious boy in hopes that he will have some memories of me. If nothing else, I hope he’ll remember how it felt to be with me, safe and so very loved.”

When we abandon planning as the organizing principle of our lives—because we’ve found a more enjoyable framework, or because we’re simply running out of time—we find that memory-making is a wonderful alternative.

I look at the photo included in her Times piece: Shirley holding Dashiell as they gaze out over the ocean, their time together dwindling, their joint memory-bank account growing flush.

💬 What do you think?

I’m curious to hear from you. What’s an especially meaningful memory you’ve banked with your loved ones? How do you make your memories indelible?

Had your own plan-in-flames experience? Taking a leap into the unknown? I’d love to hear more. Just hit “reply” to get in touch, or introduce yourself here.

Warmly,

Maddie

I loved this post and agree with it completely. My husband and have two (now adult) children, and rather than scrimp and save to send them to an expensive private college, we agreed we would send them to a cheaper in-state public college and give them a different education - travel. We took them to Ireland several times to visit distant cousins; we took them to Italy, Sicily, France, the great cities of Canada. We went to San Francisco, Chicago, Phoenix, the ocean and mountains. Dozens of trips. They know Washington, DC from repeated trips to visit an aunt and attended Obama's inauguration with 2 million of our closest friends. The kids loved it. Travel gave them enormous confidence and a sophistication they don't even realize they possess. And me? I have glorious memories of my son clowning in the British Museum, imitating statues; the sight of my daughter on a high hill overlooking Clew Bay; canoeing in Northern Canada. Lucky me. lucky us, and worth any penny.

"time together dwindling, their joint memory-bank account growing flush" ❤️ isn't that how we should approach all our engagements with the world. Thank you for pointing this out.